I look up and notice the pale white glow of the moon shining from behind the silhouette of the mountain ridge, far above us, and I watch as the thin sliver appears, shedding a faint light on our team of climbers. In this equatorial region the moon looks strange, lying upturned on its back like a dish, but it’s a welcome sight. The sun will only be a couple of hours behind it. In front of me Paul steadies himself against the slope ahead of him. He heaves his useless right leg up and plants it down on a snowy ledge. He then throws himself forward onto the leg and attempts to stand up on it, but the snow crumbles under his weight and he slips back down again to where he started.Sitting in the snow on a ledge above, Pete braces his legs, which are strapped into steel callipers, against a rock and tightens his hold on the safety rope between him and Paul. In front of me Paul steadies himself against the slope ahead of him. He heaves his useless right leg up and plants it down on a snowy ledge. He then throws himself forward onto the leg and attempts to stand up on it, but the snow crumbles under his weight and he slips back down again to where he started.Sitting in the snow on a ledge above, Pete braces his legs, which are strapped into steel callipers, against a rock and tightens his hold on the safety rope between him and Paul.

Without a word of complaint Paul steadies himself once more and tries again. This time he has more success and as he stands on the paralysed leg the snow holds long enough for him to kick his good leg in higher up the slope. In this way a precious few inches of altitude are gained. It is 5am now. We have been climbing since 1am and have so far made 400 metres of height on Dave’s altimeter. It’s another 700 metres to the summit and Paul is tiring already. The idea began back in 2000, one and a half years after the mountaineering accident that cost me my hands and my feet. I was then only just getting back into mountaineering – my ascent of Ben Nevis a few months earlier had at that time felt like my limit – but when another disabled mountaineer, David Lim from Singapore, suggested an all-disabled mountaineering expedition I was immediately keen. Pete Steane from Australia and Paul Pritchard, a Brit living in Tasmania were also easily persuaded and suddenly we had ourselves a team. There are quite a few disabled mountaineers these days, who are achieving any number of truly remarkable feats. Eric Weihenmeyer who is blind and has climbed Everest, Tom Whittaker who has also climbed Everest with one prosthetic leg, and Warren Macdonald who made an epic four week ascent of Federation Peak without legs, are some of the names that come to mind. Those are all quite outstanding individual achievements but what we wanted to do was to demonstrate to the world that being a disabled mountaineer doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to be dependent on your able-bodied colleagues. As four disabled people we wanted to go out and climb a mountain working as a fully functioning, self sufficient, independent team. The fact that none of us had ever climbed together before would only add to the interest. The search began for sponsors – the painkiller manufacturer Voltaren kindly stepping in, and for a suitable objective. After much deliberation we settled on Kilimanjaro. As the highest mountain in Africa, at 5895m, it seemed like a fitting goal and it had the added benefit of being relatively accessible. There are walking routes up Kilimanjaro but we wanted to climb it by a more challenging and less frequented route up the Credner Glacier on the northern side of the mountain. With global warming the glaciers on Kilimanjaro are receding at an alarming rate and this could be one of the last chances anyone might have to climb a glacier route in equatorial Africa. And so the Voltaren Kilimanjaro Challenge was born, although it wasn’t until January 2004 that the four of us finally arrived in Tanzania at the foot of the vast snow-capped mountain which rears up out of the African plains.

This was a good chance for us to get to know each other better in preparation for working well as a team higher up. As we left the rainforest and climbed up through heath and moorland – a region of weird giant heathers, draped with beards of hairy lichens – I talked to David, our team leader.

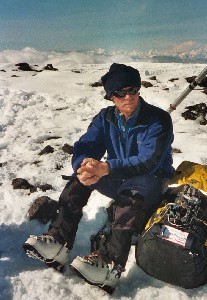

Now he walks with two orthotic splints to support his ankles and has slight palsy in both of his hands, especially when they are cold when his thumbs stop working. Dave is a natural organiser and he would talk tirelessly about plans and strategies for the mountain ahead. We spent the fourth night at an altitude of 4,600 metres, camped next to a large pinnacle of rock known as the Lava Tower, then we traversed round the mountain and descended slightly to Stirn-Moir camp at 4,200 metres. We were now in place for our summit push via the Credner Glacier. Preparations were made to leave our guides and porters behind and go for the top. Equipment was sorted, food packed, the petrol stoves tested, and the high-altitude tents checked. But the next morning we were to suffer the first of several setbacks which were to threaten the success of our climb. Paul woke an hour or two before we were due to set off to discover a distinct bubbling rattle at the bottom of his lungs when he breathed out. This, the whole team knew, was the first symptom of pulmonary oedema, an extremely serious form of altitude sickness. There was no choice but to get Paul lower down the mountain in the hope that he would recover. Pete and Dave decided to go with our guide, Safi, to carry out a reconnaissance of the Credner Glacier. Meanwhile Paul and I descended to Shira Camp at 3800 metres.

Then, in 1998, everything changed when an abseil rope dislodged a television sized block which fell and struck him on the head, smashing open his skull. Miraculously, Paul was rescued and he went on to make an inspirational recovery. But the brain damage was permanent and he was left with severe paralysis down the whole right side of his body. His right arm is now useless and only a few of the muscles function in his right leg. Thankfully his intellect remains undamaged as does his sense of humour and his dry northern wit would frequently have the whole team in stitches. Over the next two days, while we waited for Paul’s pulmonary oedema to clear up, we suffered three further setbacks. Firstly, the weather broke. The now familiar routine of sun in the morning, cloud and rain in the afternoon, and sun again in the evening was replaced by a constant torrential downpour. Above 4500 metres the rain fell as snow. Kilimanjaro is usually quite a busy mountain but this unseasonable weather washed every single climbing team down off the mountain. Except for us. The second setback was our failure to even locate the foot of the Credner Glacier, despite two recce’s. This was partly due to the atrocious weather but also due to the fact that the glacier appeared to have retreated significantly since the route was last described, leaving behind it some very difficult terrain of scree and loose boulders.

The whole expedition looked jeopardised now. One team member had altitude sickness, we couldn’t find the route and the one person who could help us do so had left the mountain, and a foot of fresh snow now cloaked the upper 1400 metres of the mountain. I personally doubted whether we could make it. Had we bitten off more than we could chew? Was it really possible for an all-disabled team to climb a mountain like Kilimanjaro? In the mess tent, rain beating steadily down on the canvas, we had a team meeting and made some difficult decisions. Our priorities were threefold, in the following order: 1. Get down safely off the mountain. 2. Stick together as a team. 3. Reach the summit of the mountain.

This fresh attempt on the summit would require a couple of extra days on the mountain but fortunately the porters were all happy to earn some extra money (although a couple of them expressed concerns that when they finally returned home their wives might be pregnant!). Thankfully Paul’s lungs cleared up and so did the weather. Two days later we had regrouped and were camped at 4800 metres at Arrow Glacier Camp making final preparations for our assault on the Western Breach and our 1am start the next morning. *

Pete has had his fair share of knocks in life. In 1982 he fell while rock climbing and damaged his spinal cord resulting in permanent partial paralysis below his waist. Undaunted he carried on climbing until a car crash broke most of the bones in his body. He had just about recovered from that when he was diagnosed with cancer in one of his kidneys and had to have it removed. Pete is still one of Tasmania’s leading climbers.

Wabunga rises still further in our estimations some time later when we stop for a rest. From under his Masai blanket he produces four mugs and a large thermos of sweet tea. We are certainly glad now that he has come. Our team struggles on. The way ahead becomes steeper and rockier and the climbing more difficult. As the sun rises the mountain casts its enormous shadow onto the distant plains.

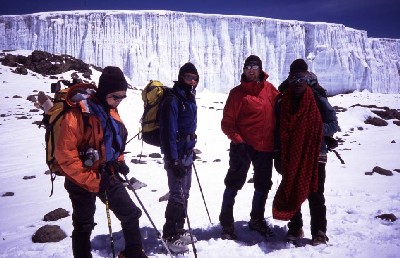

At 3pm a line of four weary climbers arrive on the broad, sunny summit of Kilimanjaro, the roof of Africa. Below and all around us is a sea of cumulus – the rest of the world is in cloud. Paul is the last to arrive, dragging his dead leg behind him. He looks like he has just run four consecutive marathons. We are all exhausted and the prospect of the long descent to the tents is almost unthinkable. However descend we must and soon we set off on that gruelling, nine hour hike back down the mountain. But that is another story. |

The first few days of the climb were straightforward and enjoyable. We had hired porters to carry our equipment and supplies as far as the foot of the steep section of the climb, so we walked with light loads up through the verdant rain forests which cloak the lower slopes of the mountain.

The first few days of the climb were straightforward and enjoyable. We had hired porters to carry our equipment and supplies as far as the foot of the steep section of the climb, so we walked with light loads up through the verdant rain forests which cloak the lower slopes of the mountain. Dave was one of Asia’s best known climbers and had just returned from leading Singapore’s first Everest expedition in 1998 when he was struck down by a rare and mysterious nervous disorder known as Guillain-Barre Syndrome. The disease nearly killed him but Dave survived, despite almost total paralysis, and fought back to recover the use of most of his body.

Dave was one of Asia’s best known climbers and had just returned from leading Singapore’s first Everest expedition in 1998 when he was struck down by a rare and mysterious nervous disorder known as Guillain-Barre Syndrome. The disease nearly killed him but Dave survived, despite almost total paralysis, and fought back to recover the use of most of his body. Paul is a pretty redoubtable character. He was once one of the world’s foremost climbers, making many bold and audacious first ascents at home and all over the globe.

Paul is a pretty redoubtable character. He was once one of the world’s foremost climbers, making many bold and audacious first ascents at home and all over the globe. The third setback occurred following our second recce when our guide, Safi, and his assistant, Charles, became snowblind after a day walking in the snow without sunglasses. The poor guys were in such pain that they decided to descend the mountain in the middle of the night with a couple of the porters for assistance.

The third setback occurred following our second recce when our guide, Safi, and his assistant, Charles, became snowblind after a day walking in the snow without sunglasses. The poor guys were in such pain that they decided to descend the mountain in the middle of the night with a couple of the porters for assistance. Beyond these priorities we were going to have to make compromises and so we decided to abandon our attempt on the Credner Glacier and go instead for the much more popular, yet still very challenging (particularly under a foot of snow), Western Breach Route. We also decided, partly for logistical reasons, partly because of Paul’s altitude problem, to climb with a guide, Cornelli, who was one of Safi’s assistants.

Beyond these priorities we were going to have to make compromises and so we decided to abandon our attempt on the Credner Glacier and go instead for the much more popular, yet still very challenging (particularly under a foot of snow), Western Breach Route. We also decided, partly for logistical reasons, partly because of Paul’s altitude problem, to climb with a guide, Cornelli, who was one of Safi’s assistants. At about 7am the sky begins to brighten and as the light of the stars fades away, so do the twinkling lights of Moshi, the small town far below us at the foot of the mountain. We’re at 5400 metres now and keeping up a slow but steady pace. Dave takes the lead, with Cornelli, picking out the route. Then comes Pete, holding Paul’s rope where necessary.

At about 7am the sky begins to brighten and as the light of the stars fades away, so do the twinkling lights of Moshi, the small town far below us at the foot of the mountain. We’re at 5400 metres now and keeping up a slow but steady pace. Dave takes the lead, with Cornelli, picking out the route. Then comes Pete, holding Paul’s rope where necessary. Behind Paul is Wabunga, our cook. Climbing in trainers and wrapped against the biting cold only in a Masai blanket, we were initially mystified why Cornelli should choose Wabunga to accompany us, but he has truly been a rock, climbing directly behind Paul at all times, halting his frequent slips and giving him a push up where necessary.

Behind Paul is Wabunga, our cook. Climbing in trainers and wrapped against the biting cold only in a Masai blanket, we were initially mystified why Cornelli should choose Wabunga to accompany us, but he has truly been a rock, climbing directly behind Paul at all times, halting his frequent slips and giving him a push up where necessary. I climb mainly at the back. This is an unusual experience for me. As a disabled climber I am very used to being the centre of attention, but today I am just one of the team. Paul requires more assistance than me and for him this climb is twice as much effort. And despite coping so valiantly with his disabilities, he tends to receive far less credit and attention than I do. That’s because his disability, unlike my amputations, are not immediately visible. His brain injury is difficult for others to understand. Mostly people just think he’s drunk. For me, he is the greatest hero of this climb.

I climb mainly at the back. This is an unusual experience for me. As a disabled climber I am very used to being the centre of attention, but today I am just one of the team. Paul requires more assistance than me and for him this climb is twice as much effort. And despite coping so valiantly with his disabilities, he tends to receive far less credit and attention than I do. That’s because his disability, unlike my amputations, are not immediately visible. His brain injury is difficult for others to understand. Mostly people just think he’s drunk. For me, he is the greatest hero of this climb.